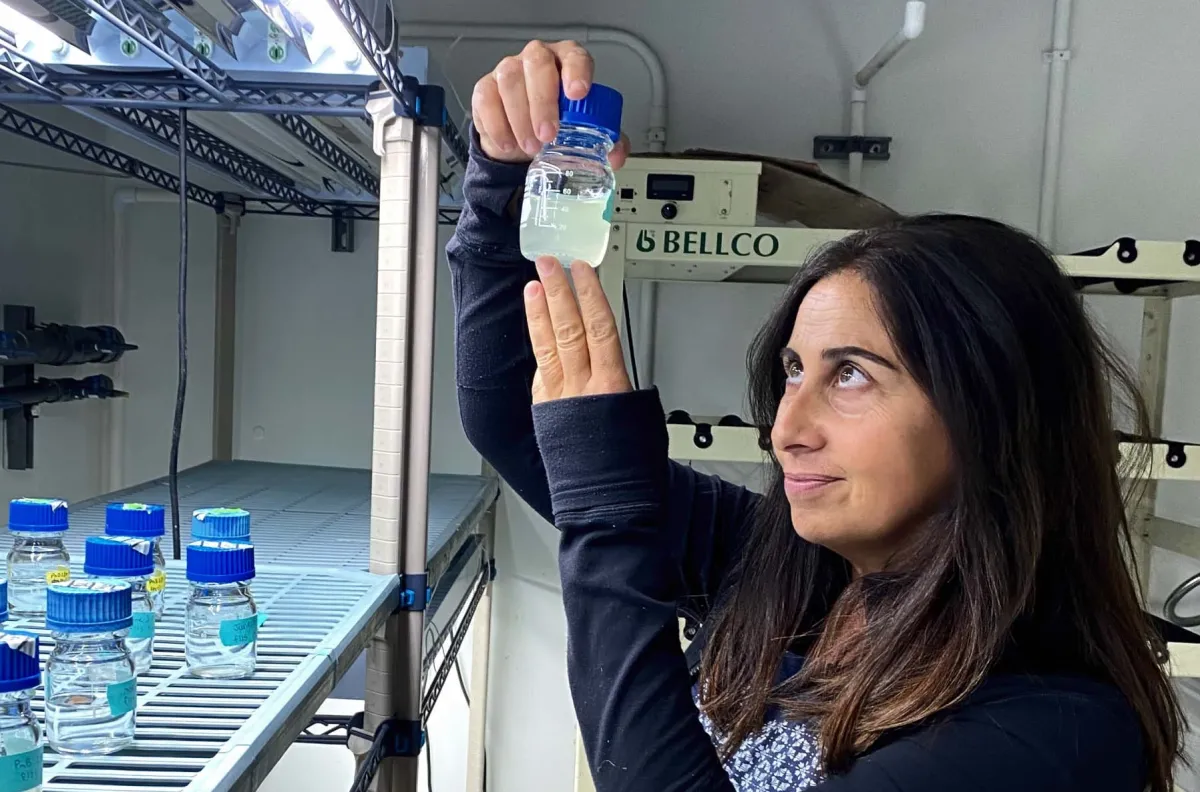

UC Santa Barbara (UCSB) professor Débora Iglesias-Rodriguez is investigating how to harness the power of the oceans to lower CO2 levels without adverse effects on marine life.

The most important action we can take to combat climate change is to stop adding carbon dioxide (CO2), which is responsible for warming our world, to the atmosphere.

But that won’t be enough.

Over the coming decades, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), we will also need to remove excess quantities of CO2 already in the atmosphere.

That’s where UC Santa Barbara (UCSB) professor Débora Iglesias-Rodriguez comes in. She’s investigating how to harness the power of the oceans to lower CO2 levels without adverse effects on marine life.

The ocean acts as a “carbon sink,” meaning it naturally absorbs 25% of all carbon dioxide emissions, according to the United Nations.

As a biological oceanographer, Iglesias-Rodriguez knows well the role that oceans play in keeping Earth’s greenhouse gasses balanced, through a natural process called weathering. Weathering occurs when rain absorbs carbon dioxide as it falls, becoming slightly acidic. This rain breaks down rocks on land, dissolving carbon-rich materials that wash out to sea. These materials add alkalinity (the capacity to neutralize acid) and modify the chemistry of seawater, locking carbon dioxide away from the atmosphere for millennia.

One day, we hope to harness the oceans to remove a billion extra tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere per year using not only our method but many approaches to remove carbon dioxide.

—Débora Iglesias-Rodriguez

Yet natural weathering happens too slowly to absorb our current carbon dioxide emissions, which have dramatically increased during the last century. Iglesias-Rodriguez and her team are part of a growing field of scientists and researchers trying to accelerate this natural process through a technique called enhanced weathering. This is accomplished by adding minerals, in crushed or liquid form, directly to seawater.

By boosting alkalinity, enhanced weathering could also start to reverse ocean acidification that can harm coral reefs and shell-building organisms like oysters and other mollusks — helping to restore balance.

Iglesias-Rodriguez wants to understand the effectiveness of enhanced weathering and any potential risks to the environment and marine life, particularly to a group of calcium-carbonate shell-building phytoplankton called coccolithophores. These phytoplankton, or one-celled marine plants, rely on carbon not only for photosynthesis, but also for forming intricate structures of chalk (calcium carbonate) called coccoliths, which surround its cells.

She and her UCSB team conduct experiments at a variety of scales, inside the lab and outside in large tanks, using natural populations of organisms collected from the Santa Barbara Channel. They’re exploring, in careful detail, the impact of adding alkaline rock, a type of material that mimics natural weathering, on plankton communities. The work is part of a project supported by the nonprofit Carbon to Sea Initiative — one of several partners CZI funds to research, develop and scale climate and clean energy technologies.

As we celebrate World Oceans Day and the importance of protecting our blue planet, join us for a peek into a day in Iglesias-Rodriguez’s life.

Early Morning Insights

The field of carbon dioxide removal is still very young. So, as an expert laying the foundations for using the chemistry of oceans to absorb carbon dioxide, I think it’s important to be part of the emerging conversation. On most days I get up very early, before the sun rises, to write blogs, to compose emails, to share and trade ideas with others. I find that my brain functions particularly well for writing at 4:30 a.m.

I authored a book on the future of marine life in a changing ocean that explores big issues such as warming, hypoxia (low oxygen levels), oil and plastic pollution, and ocean acidification. We know that carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere have been rising at a rate unprecedented in the recent history of Earth, and that much of this gas ends up in surface waters.

While this might provide a tiny boost to photosynthetic organisms, it also acidifies the oceans, altering the ability of some organisms, including some coccolithophores, to form shells. Oceans have only so much ability to prevent this situation from spiraling out of control, and we’re already seeing other climate change impacts such as bleaching of coral reefs and the expansion of zones of low oxygen in the oceans. That’s why, although I once believed that it was unethical to intervene in the oceans, I now think it’s unethical not to.

Later in the morning, I drop my son off at school. His generation will have to deal with the effects of a changing world if we don’t get this right. Even though he’s only four years old, he’s very curious about my work. He tells me that he wants to be a marine biologist, like me! A few times a year, I visit his class in Santa Barbara with pails of sea creatures for show-and-tell. Every year I travel to Spain to see my family and I have been a regular in my niece’s school, where the class is now well versed in themes like ocean acidification and warming.

An Afternoon of Research, Experiments and Celebrations

nce in my office, I’m visited by members of my team, including lab specialist Sylvia Kim. She’s working on small-scale experiments that test whether adding minerals to seawater can stimulate the growth of aquatic microorganisms that use carbon to build their calcium shells. Her work involves the analysis of carbonate chemistry in seawater to determine the carbon dioxide removal-potential of adding minerals that increase alkalinity. Weeks of painstaking preparation go into these experiments. Even so, road bumps pop up. We troubleshoot.

In our lab meetings, graduate student James Gately might talk about his larger-scale mesocosm experiments: tanks that allow us to investigate different treatments outdoors, in the waters of the Santa Barbara Channel. To discuss his progress and challenges, we break into problem-solving groups that include our army of undergraduates. Ever since I pivoted my research to focus on carbon removal, I’ve been all but overwhelmed by interest from college students who want to join the lab. It’s inspiring to see the next generation of scientists be so enthusiastic.

Now that we can return to being social, we plan to celebrate every science success by getting together at our favorite local beach. Over the years, we’ve developed new ways to measure calcification in marine organisms and variability in dissolved mineral concentrations across the ocean. We’ve examined rare plankton blooms, studied how the creatures respond to changing temperatures, and even contributed to a study led by Rutgers University uncovering the role plates of coccolithophores can play in viral infections.

Ongoing, Interdisciplinary Collaboration

Collaboration is essential to our efforts. To move this work forward, we partner not only with other oceanographers and biologists but also with engineers and entrepreneurs. Much of my day is spent on Zoom calls with this community, the people who help build our equipment or think about how to carry out even larger-scale experiments. Ultimately, we hope to lead efforts to test our ideas out on the open seas. One day, we hope to harness the oceans to remove a billion extra tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere per year using not only our method but many approaches to remove carbon dioxide.

Science As Art

This science has taken me to unexpectedly creative places. I once collaborated with my artist mother, Rosa Seoane, on a project coordinated by Cape Farewell’s director David Buckland that culminated in an exhibition featuring coccolithophores amongst other climate-ocean relevant themes.

She created illustrations in chalk, the same material that these creatures use to build their shells. We’ve also worked together on an expedition to Svalbard, in the Arctic Ocean. Connecting with the public is important, which is why I share my work by giving talks in local venues, visiting schools and engaging with local entrepreneurs. We’re all in this together; we all share this beautiful blue planet.