Photo Credit: Michal Vaško / Pexels

From the Santa Barbara Independent

In early May, I joined a group of public officials, environmentalists, and reporters on an ecotour of the Anacapa Island State Marine Reserve, hosted by UC Santa Barbara’s Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory.

Our mission was to see firsthand what lurks in these protected zones — which oftentimes prohibit fishing and other extractive activities to safeguard marine life — and to understand what’s at stake as potential policy changes loom.

We were all in awe at this sheer abundance of life.

Changing the Network

Marine protected areas are like “national parks under the sea,” in the words of Dr. Douglas McCauley, the director of the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory.

He said that, in MPAs, not only do fish have the chance to grow larger, but they also generate more eggs. Their protected neighborhoods contain what he thinks of as “underwater wolves and bison,” like the giant sea bass.

California completed its first 10-year review of its MPA network — covering 16 percent of state waters — in 2022. It showed that these underwater sanctuaries help biodiversity flourish and provide multiple climate benefits (such as sucking carbon out of the atmosphere, increasing resilience to warming ocean temperatures, and buffering coastlines against sea-level rise).

Spillover from MPAs — e.g., oblivious lobsters waddling outside MPA bounds — can even increase catch in neighboring fisheries, sometimes by more than 200 percent.

According to a paper published by the Benioff Laboratory, MPAs are also pretty valuable for recreational users and businesses, with marine and coastal tourism contributing approximately $26 billion to the state’s economy each year.

Recently, MPAs have been in the spotlight due to the state’s call for petitions to expand, add, or subtract from the coast’s MPA network. Factor in that more ocean real estate is being eyed for activities such as deep-sea mining and offshore wind development, and the conversation around these zones is being amplified.

The state is now advancing this process of “adaptively managing” its MPA network. It will consider adopting an evaluation framework for petitions this summer.

Controversy in the Channel

The Santa Barbara Channel is home to 13 MPAs. But the idea of adding more is controversial.

While new MPAs could benefit marine life, they may also limit commercial fishermen’s ability to put food on the table, not only for their families, but also for others.

Fishermen have argued that the state’s regulations are heavy-duty enough as is — no need for making more of their workplace off-limits.

The Commercial Fishermen of Santa Barbara (CFSB), for one, want to help protect marine habitats, but feel that they are gradually being pushed to fish in “smaller and smaller areas,” in the words of their president, Chris Voss.

Voss said they do not, by any means, think that existing MPAs should be eliminated or downsized. But, he added, they are opposed to expanding the network because fishermen are “under constant threat of losing additional fishing grounds from a host of different initiatives,” such as offshore wind energy.

It’s a multifaceted conversation.

Sandy Aylesworth, a director with the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC), who dived with us on the trip, gave a mini-speech before our boat, the Spectre, set off from the Ventura Harbor.

According to Aylesworth, conservation proposals could add up to 2 percent, or about 44,000 acres, to the state’s MPA network.

New Proposals

Around Santa Barbara County and the Channel Islands, there are 11 petitions to expand or improve MPAs. On the flip side, there are nine that seek to eliminate or reduce them.

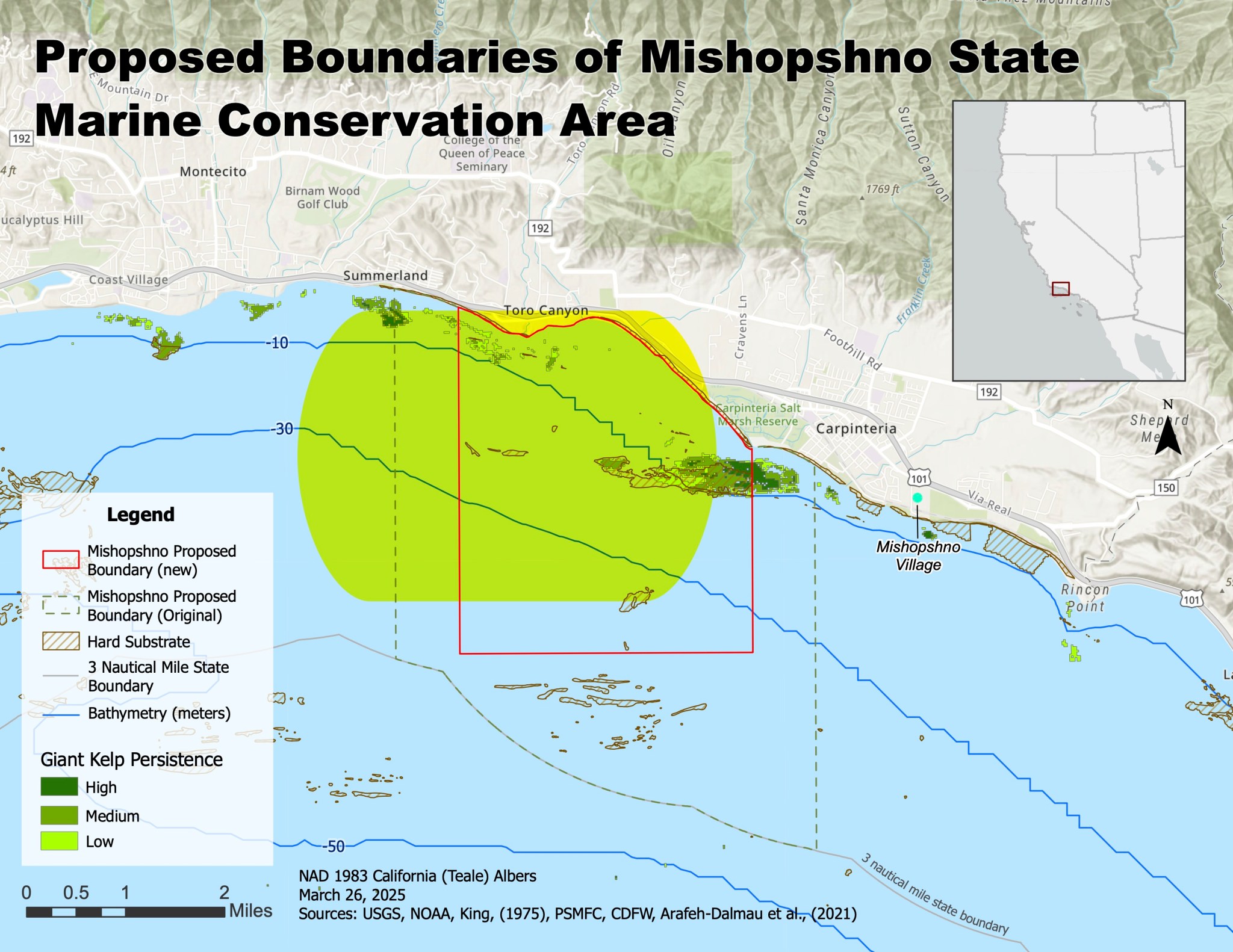

For example, the NRDC, in collaboration with the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians and the Environmental Defense Council, are proposing a new MPA in the coastal waters of Carpinteria.

The group says that the Carpinteria coast is home to a “long, rocky reef” that supports kelp forests, sandy habitats, and marine life within a relatively small area, including a hot spot for juvenile white sharks. And the adjacent coastal village, Mishopshno, after which the proposal is named, was a boat building site and “thriving community” where the Chumash built tomols. As such, it would be a new tribal-managed MPA in the region, and would likely “benefit populations of targeted species, protect high levels of biodiversity, and promote ecosystem resilience,” according to the proposal.

The MPA would cover nine acres and prohibit the take of all living, geological, or cultural marine resources, except for the recreational take of finfish from shore using hook-and-line. Non-extractive activities such as swimming would also be allowed; the Chumash would be allowed to fish with the use of hand-based equipment; and scientific research could be conducted.

The Misopshno State Marine Conservation Area. Photo Credit: NRDC

The group modified the proposal after public outreach, shrinking the MPA from 18 to nine acres and allowing recreational fishing. “The proposed boundaries of the SMCA [state marine conservation area] were informed by extensive outreach and discussions with local Tribes and fishers,” the proposal reads. “The proposed boundaries meet a difficult-to-achieve compromise between upholding science-based size and area criteria, protecting critical habitat and promoting connectivity for the broader network, while allowing continued fishing access to important local fishing areas.”

Some petitions, on the other hand, are proposing to give fishermen more leeway within existing MPAs. That includes the take of species in certain areas, such as the California Sea Urchin Commission’s proposal to allow for the take of urchins in nine SMCAs, including around Anacapa Island. This would expand the areas where commercial fishermen can harvest urchins and boost the production and sale of uni, the edible part of the urchin that has become a popular California delicacy.

Voss, for one, thinks this is a “common sense” proposal. Sea urchins have overrun certain areas of the coastline, creating urchin “barrens” devoid of life. Culling the population could curb the harm and, since they are caught by hand, does not include adverse effects like bycatch, he said.

But it will be a long time before any significant changes are enacted. Right now, the state is still thinking about how to even go about reviewing the petitions. In August, the California Fish and Game Commission will consider the approval of a framework to evaluate the changes and move on to the next steps of managing the network. The commission will start making decisions regarding various MPA proposals along the coast beginning this November.

To learn more about the different petitions, visit Marine Protected Areas Petitions.

More to read at SB Independent