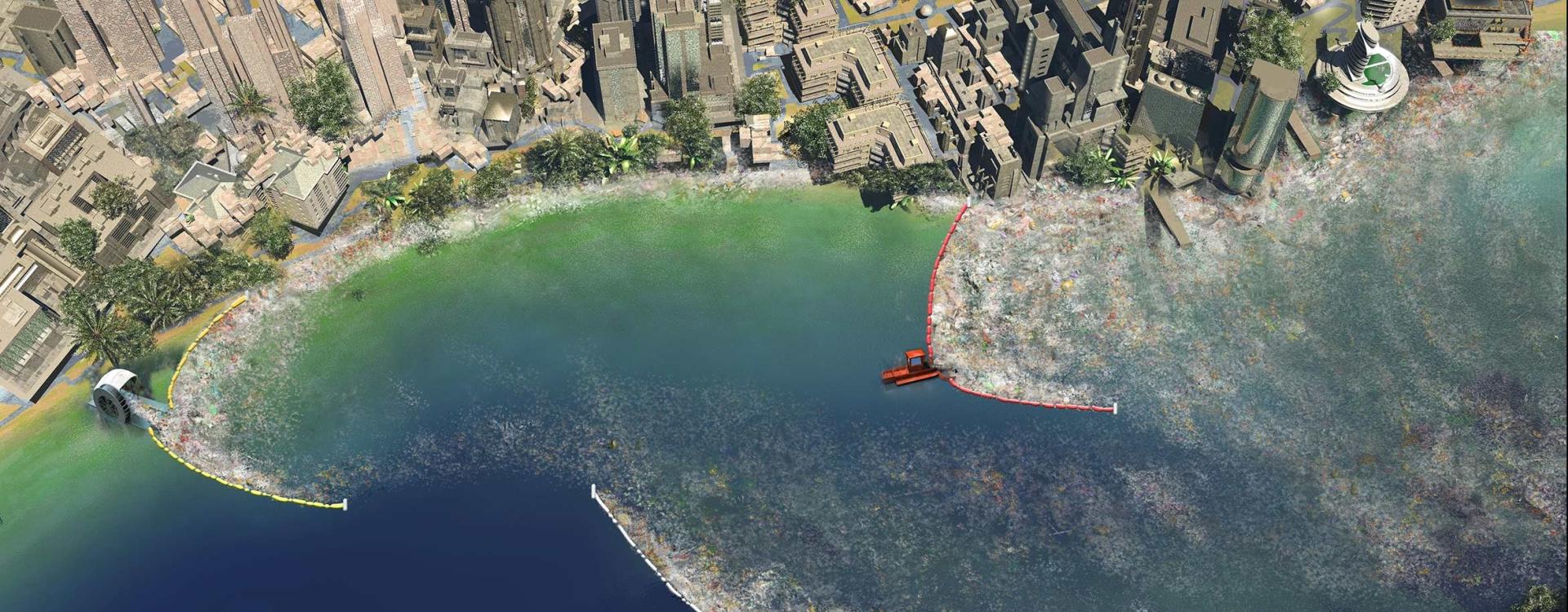

A depiction of various river plastic collection technologies utilized for data collection. Photo Credit: Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory

A groundbreaking global study led by researchers at UC Santa Barbara’s Marine Science Institute (MSI) reveals how plastic pollution travels through rivers into oceans — and, crucially, how to stop it at its source.

Published in the Journal of Environmental Management, this study presents one of the most comprehensive datasets ever collected on riverine plastic pollution. Spanning three years, four continents, and eight countries — Mexico, Jamaica, Panama, Ecuador, Kenya, Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia — the research tracked the types, sources, and movement of plastic waste in rivers. It was conducted by UCSB’s Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory in partnership with local organizations and community leaders.

“This work helps us move beyond estimates and models,” said Dr. Douglas McCauley, Professor of Ecology at UCSB, Principal Investigator at MSI, and Director of the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory. “We now have on-the-ground data that shows what kinds of plastics are in rivers, where they’re coming from, and which local solutions are working.”

Leading the data analysis was Chase Brewster, Project Scientist at MSI, who highlighted the project’s community-first approach. “Each river site was independently managed by local partners,” Brewster explained. “They didn’t just collect waste — they implemented cleanup technologies, collaborated with governments, educated communities, and gathered high-resolution data.”

This is about turning off the tap of plastic pollution, not just cleaning up after it. It’s science with a purpose — and a reminder that real, lasting change comes from empowering the communities most affected.

Together, these partners form the Clean Currents Coalition, a global initiative powered by MSI and the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory. Over three years, they removed 3.8 million kilograms of debris from rivers — equivalent to 380 million single-use plastic bottles. About two-thirds of this was macroplastic, large items posing major threats to marine ecosystems.

Extrapolating these results suggests nearly 2 million metric tonnes of plastic may flow from rivers into oceans annually worldwide — a staggering amount with serious implications. The study also evaluated policy impacts: Kenya’s plastic bag ban correlated with significantly fewer bags in rivers compared to Vietnam, where such bans have yet to take effect.

Another significant insight involves the informal waste-picking sector. In countries like Indonesia, where informal recycling networks are organized and active, rivers contained fewer recyclable plastics. “Supporting these waste-pickers with policy, fair pay, and protections empowers them to play a vital role in keeping plastic out of waterways,” Brewster said.

Molly Morse, Director of the Clean Currents Coalition and Senior Manager at the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory, emphasized the hopeful message behind the research: “In a time when plastic pollution feels overwhelming, this project shows that community-led, river-by-river efforts can generate the data and momentum needed for lasting change.”

The research team made four key recommendations:

- Create economic value for plastic waste via policies like bottle deposits and recycled content mandates.

- Invest in waste management and recycling infrastructure, including formal support for informal waste-pickers.

- Improve standardized, local data collection to track the effectiveness of interventions.

- Support local and global policy frameworks, such as the United Nations’ emerging treaty to end plastic pollution.

The study’s entire dataset is publicly available to encourage further research and innovative solutions. “We hope others build on this foundation,” McCauley said. “This data can inspire new science, policies, and community action.”

Beyond cleanup, the project sought to make lasting impacts on communities. In Panama, teams deployed the country’s first autonomous, solar-powered trash wheel to collect river plastics while generating data to inform policy. In Mexico and Kenya, cleanup sites were converted into green public spaces promoting health, jobs, and civic pride.

Since 2020, the Clean Currents Coalition has removed over 7.3 million kilograms of river debris worldwide, while supporting infrastructure, education, and environmental restoration — especially among youth.

Original reporting by Debra Herrick, “How plastic pollution flows from rivers to oceans — and how to stop it.” The Current, UC Santa Barbara, 2025.