Yellow fever infections are increasing as the disease spreads across the growing boundary between forested and urban areas. Photo Credit: Thiago Japyassu / Unsplash

As human development pushes deeper into previously undisturbed ecosystems, environmental disruption is increasingly translating into public health risks.

Researchers at UC Santa Barbara examined how land-use change is contributing to rising cases of yellow fever among people living in the Amazon basin. Their study, published in Biology Letters, shows that expanding contact zones between forests and urban areas are strongly associated with human infections.

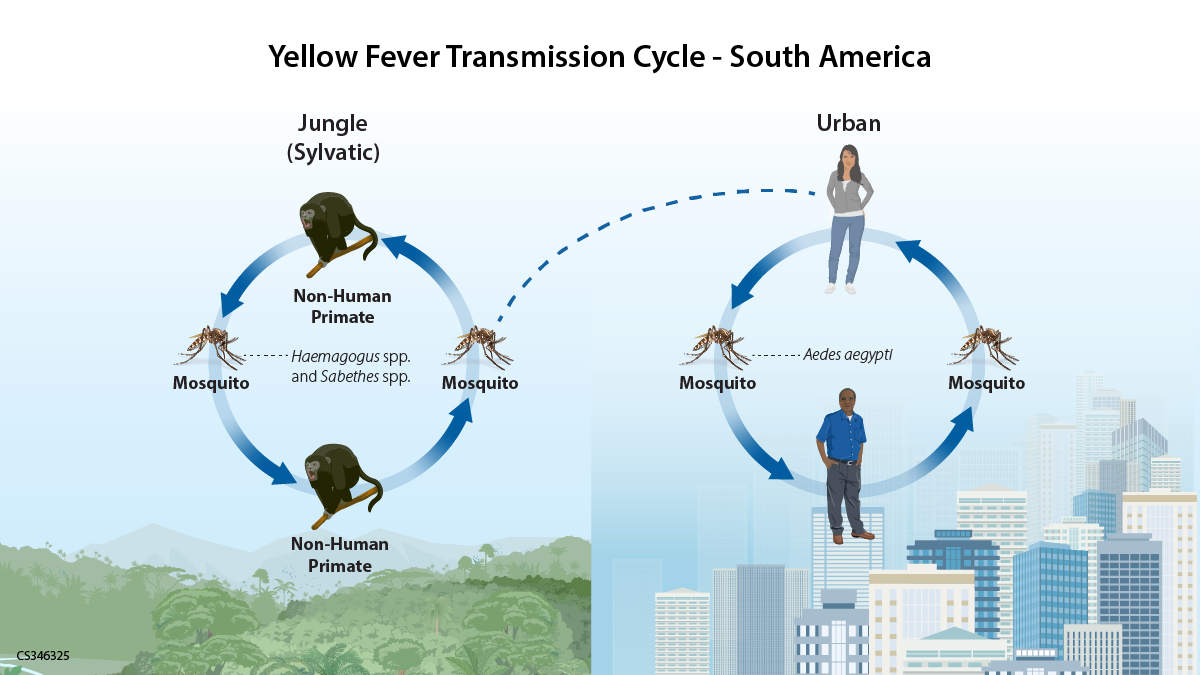

“Yellow fever is increasingly infecting humans when they are living close to the forest,” said author Kacie Ring, a doctoral student co-advised by Professors Andy MacDonald and Cherie Briggs, both Marine Science Institute Principal Investigators at UC Santa Barbara. “And this is because humans are encroaching into areas where the disease is circulating naturally, disrupting its transmission cycle in the forest."

Yellow fever had become rare in South America following major public health campaigns in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, largely persisting only among wildlife in forested regions. Today, however, researchers warn that conditions may once again support sustained urban transmission.

Land use and spillover risk

Ring, MacDonald and junior research specialist Terrell Sipin analyzed yellow fever case data from Brazil, Peru and Colombia alongside land-use information from the MapBiomas Project. They assessed how infection rates related to forest patch size, forest edge density and the extent of forest–urban contact.

While forest fragmentation alone showed some association with spillover risk, models that accounted for human settlement patterns revealed that proximity between cities and forests was the strongest predictor. A 10% increase in forest–urban adjacency raised the probability of spillover by 0.09 — equivalent to a 150% increase in annual events. On average, this borderland is expanding by about 13% per year.

“It was a little surprising that the ecology wasn’t more predictive of the actual transmission to humans,” said MacDonald, a professor in UCSB’s Bren School of Environmental Science & Management.

“It seems the thing that’s causing the disease spillover is that humans are moving closer to the forest edge,” Ring said.

Forest margins often support higher mosquito activity due to warmer temperatures and standing water, increasing the likelihood of human exposure.

Currently, people get yellow fever only when it spills over from the forest (dotted line). But human-to-mosquito-to-human transmission in cities (right) could be making a comeback. Credit: CDC

A preventable resurgence

Yellow fever once fueled devastating outbreaks in the Americas and contributed to failures such as the early French effort to build the Panama Canal. “They were losing workers left and right,” MacDonald said. “Over 20,000 workers died.”

Urban transmission cycles were eventually eliminated through vaccination and mosquito-control campaigns by the mid-20th century. “But a campaign like this would never be executed in the modern day,” Ring added. “Widespread use of DDT led to long-term storage in the soil and contamination in drinking water.”

Recent World Health Organization reports show cases continuing to rise, with 212 confirmed infections in 2025 — more than triple the total reported in 2024. Because yellow fever is now relatively rare in the Americas, vaccine stockpiles are limited. “So, if cases change suddenly, then we’re unprepared to deal with it,” MacDonald said.

This is a totally preventable disease. There’s a vaccine that’s been widely available for 80 years.

The team plans to continue studying how land-use change affects infectious disease risk. MacDonald hopes the research will help guide development strategies that better protect both people and ecosystems. As Ring put it, “these emerging infectious diseases are indicators of broader environmental issues.”

Adapted from original reporting by Harrison Tasoff, “Old diseases return as settlement pushes into the Amazon rainforest,” The Current, UC Santa Barbara, 2026.